Stories

This page is for any Stories that have been submitted. We hope that you will visit this page often to not only remember your loved one, but the loved ones of others who have been shared here.

If you would like to submit a story to be included on this page please email us at secretary@sosbsa.org.au. Could you please include the first name, birth and death dates for your loved ones. All submissions will be added by one of the SOSBSA site administrators, so will be checked prior to being uploaded, and this will ensure that there is no offensive material on these pages.

Steven Daniel Raun

13/03/1982 - 20/06/2014Born Moe, Victoria

Died Annerley, Queensland

Steven was a simple, loving, generous young man. He had a creative flair for his cooking and photography. He adored his two little nephews, Oskar and Jasper, and longed for the day when he would have children of his own.

He had been plagued by depression and anxiety since his late teens which he was never able to conquer. Nonetheless, I met him whilst receiving treatment for similar problems and realised I'd met my soul mate. We spent 3 and a half years together, deeply in love, through incredibly good and horrendously bad periods in both of our lives. Whilst the potential of suicide was always there in our lives, the shock of actually finding my darling Steven's body was not diminished in any way.

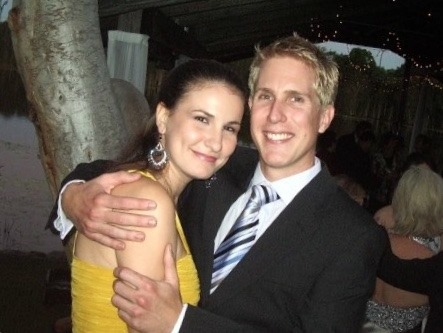

James Pritchard Leslie – As told by his wife, Lauren Leslie

I’d like to tell you about my husband, James. I don’t know where or how to start so I guess I will start from his very beginning…

James Pritchard Leslie was born at Brisbane’s Mater Hospital on 16th May 1981, the first-born son of Ann Louise and Anthony Leslie. His dad said he came out ‘all nose and no chin’. He was given the middle name Pritchard in honour of his mother’s maiden name and his grandfather, affectionately known as ‘Pritch’. Sadly, I didn’t get the chance to meet Ann and Pritch, but I knew that they were very precious people in James’ life. It is a great comfort to me, his family and friends to know that he now rests with them at Dunwich Cemetery on Stradbroke Island.

I met James in August 2007 on a Sunday afternoon at the Pig ‘n Whistle. I rarely went to the Pig ‘n Whistle, and I never went out with freshly washed, and therefore, frizzy hair. But that day I did. And there he was. It was his beautiful blonde hair that caught my eye, and his unmatched skill of conversation that charmed me. He took my number, he called, we started dating, and we fell in love. He was the most gentle, kind and loving person I have ever met, and the day he asked me to be his wife I thought my life was made.

James was witty and clever. He was inquisitive and interested. He loved to watch documentaries and learn more about the world and everything that was going on in it. And he loved to read. It was like he couldn’t read enough. He’d read several books at once and happily switch between them. He was a terrible dancer with absolutely no sense of rhythm, but that never stopped him getting up off the lounge and asking me to dance in an ad break. He’d speak of his friends and family, especially his brothers, as if they were celebrities. His love and admiration of them shone through his words and actions. He hated saying ‘no’ to anyone, especially me. So he wouldn’t. That’s how we came to get our first dog together. He was generous, he was warm, but I think his father described him best when he said at the funeral, “James was love”.

It’s hard to talk about James’ illness. It’s certainly not what defined him, but it is a part of his story and it’s what took him from me. I also believe that James would want me to share this part of his life, as James wanted to use his life to help other people. When he died, James was undertaking his third and final year of a Public Health degree. He wanted to play a role in improving health services and health education to ensure people could live healthy and fulfilling lives. He particularly wanted to play a role in improving services and awareness of mental health. He’d speak of trying to get people to view mental health care as just as important as physical health care. He hoped that one-day getting a ‘mental health check-up’ would be just a routine as a physical or dental check-up.

It wasn’t until I started living with James that I came to learn of his depression. It was something that he worked so hard at trying to hide. And he did a very good job. It was such an integral part of James’ nature to make other people feel safe and secure in his presence. He didn’t want people to ever worry about him, and if they did he’d take it as a failure. When I met James he told me he was due to finish a science degree that year. When the end of the year quickly came around I was told it would be another six-months. And when six months was up I started asking more questions. His reaction to those questions was the first time I ever saw James behaving in a way that was troubling – the trembling, the pacing. It was from that point onwards that James began to share with me his struggle with depression. He shared with me the pain he sometimes felt inside, the feelings of failure and worthlessness, and the shame and guilt he felt for letting it ‘hold him back’, and not simply ‘getting over it’. Whilst he couldn’t exactly pin point precisely when he started feeling this way, he could remember being aware of these feelings when his mother passed away in January 2003.

James would often have trouble articulating what he was feeling. That’s one of things that really hits home for me just how much this disease can stifle a person. James was an exceptional communicator. He loved to talk and had the profound ability to disarm even the most guarded person and have them happily chatting away with him within minutes. When James would talk to you it became clear how sharp his intellect was, and he’d describe things in such complete and perfect ways. But when it came to his depression and the feelings he kept hidden inside, he’d struggle to get beyond “I’m just so tired”.

From that point on, James, with the support of his family, friends and colleagues, started to try and confront his depression. He was seeing two mental health workers, was taking medication and our lives became very centred around supporting James’ mental health. Please don’t read his story as a deterrent from getting professional psychological help. James wouldn’t want that. We both knew it was the right thing to do, and it did, in many ways, help us through tough times. His story demonstrates the enormous power of mental illness.

I won’t lie. Living with James’ depression was hard. At times it was so frustrating to see him fall into episodes of such despair, especially when he would be so hard on him himself and speak of himself in such a way that made it clear that he couldn’t see all the good and all the beauty that everyone else could see. And that is not an exaggeration – everyone that came to know James came to love him. No one disliked James because he made it impossible to. This horrible disease is so cruel to take such an exceptional and beautiful human being and convince them to end their life.

I want people to know that I am not ashamed of my husband’s suicide, and I’m not ashamed that he suffered with depression. I am proud to be his wife, and I’m proud of who he was, or, as I believe, of who he is. I consider myself so lucky to have known him. Yes, there were hard times, but there were many more good times, and that is what I hold onto, that was James. I view this disease as just as real and serious as any other physical disease, and I want others to come to understand that too. Depression is physical. One’s mind, after all, comes from the brain, and the brain controls everything. But most of all I want people to know that this disease doesn’t have to be terminal, as it was in my husband’s case. If you think you might be depressed, or just can’t seem to shake off a bad feeling please let someone know and talk about it. Even if you can’t say much more than “I’m not ok right now”, the people you love will take it from there. Don’t be ashamed of how you feel, and don’t be ashamed to ask for help. Screw shame! Your life is precious! There are people out there able and willing to help if you let them in.

LETTER TO A GRIEVING MOTHER NEWLY AFFECTED BY SUICIDE

Dear

Sister,

The Hard

Stuff:

I’m not

going to pull any punches here; I am going to tell you the truth because this

journey you’re on will last for the rest of your life.

The way you

feel now, believe me when I tell you that you’re going to feel just as bad, and

worse, in the future. The pain will always be there. There will be times when

A: you wished you’d never gotten out of bed and B: you simply cannot get out of

bed.

Your hair

might still be falling out four months later.

Sometimes

you will feel as if you’re going crazy. You will definitely feel as if you live

in a bubble. There will be days when you won’t even open up the house, let

alone go outside.

Sometimes

your behaviour might be considered by others to be bizarre. You will question

your own actions. To the outside world (other people) you might come off as

being drunk, but this is because you still won’t sleep properly and fatigue

will follow your every footstep. You will question your driving ability and

safety to other road users due to this never-ending fatigue.

After four

months you will still have bursts of anger. You will still be less patient,

less tolerant and less caring. When someone tells you that they’ve had a bad

week because their kettle has blown up, their egg poacher doesn’t work anymore

and their fridge is on the blink, you will want to laugh like a crazy woman and

slap them in the face. You will take that anger out on faceless organisations,

lazy or rude shop assistants and stupid motorists.

At some point

you will shut yourself off from the rest of your family, who will then realize

that you’re not as “strong” as they thought.

You will no

longer cook extravagant, delicious foods; you will be flat out making toast.

Cigarettes, coffee and paracetamol will still be at the top of your grocery

list.

You will

lose a lot of your old friends. You will become very angry at them when they

text you once in six weeks to ask how you’re going. You will take their numbers

out of your phone and decide that they are not worth the effort.

If you’re

not in a job that you love, you are going to struggle.

You will

lose those everyday anxieties such as minor weight gain, how to get bills paid

on time, keeping up with housework because, quite simply, you will not give a

flying hoot anymore.

That Uni

degree you were two months from finishing when your child died will be put off

for awhile, then you will decide to finish it as it’s been going on for four

years, but really you don’t care if you ever work again. You will think that a

fast food driveway attendant is about all you can cope with.

Your weight

will go up and down because you will have days of not having an appetite and

days of comfort eating. The television, chocolate and ice-cream will become

your best friends.

Your house

will never be completely clean again. The weeds will stay where you put them;

two inches from where they were growing. The pile of clothes on the bedroom

floor will become bigger before you make the effort to put it all away. The

free newspapers will stay on your front lawn all week, till garbage day. In

fact, that newspaper company will become one of the faceless organisations that

you take your anger out on. How dare they litter your yard with their rubbish?

You will demand that they stop delivering; they will tell you that your address

will no longer be on their list, but the newspapers are still being thrown

amongst those weeds. You will gather them up, put them in your car and

fantasize about slamming them down on their reception counter, telling the receptionist

that your world is falling apart, please don’t make it any harder.

Everywhere

you go, you will still be reminded of the child you lost; driving by the skate

park, the cinemas, Hungry Jacks, the shop where he bought that ridiculous bong.

You avoid the music store and 3pm at every school. You will still wish that you

could go back to their babyhood and do it all again, but very differently.

You will

always (and I mean forever) feel devastated and worried because you cannot ease

the suffering of your other children.

You will

start making little shrines to your lost child all over the house and plan a

grand room for meditation filled with your child’s photos and belongings. You

will still hang onto those belongings and still cry your heart out.

The Easy

Stuff:

Sorry, but

there isn’t any. Time does not heal this wound. Your child’s suicide will

affect every aspect of your life. It will change your soul. The pain, grief and

sadness will never go away. You will never “find a way to live with it”,

because you will never accept it. You will continue to ask yourself why; you

will continue to ask your child why. You will continue to cry bucket loads.

I have been

told that there are three outcomes for survivors of suicide. These are that the

survivor will lie down and never get up again, the next is that they will get

up, but their life will be forever empty and lastly, that the survivor will go

on to help others with the research, education and wisdom that they have gained

from their experience of losing their child. I hope that you can become part of

that group that rallies and helps others.

Please

leave this letter lying around somewhere in the hope that it may be read by a

child who is thinking that suicide is the only answer. Maybe they will have a

light bulb moment and reach out before devastating their whole family.

Love

Forever,

Join us on Facebook

SOSBSA has over 15

Join in this supportive on-line support group and share your experiences with others who understand. Just click the title.